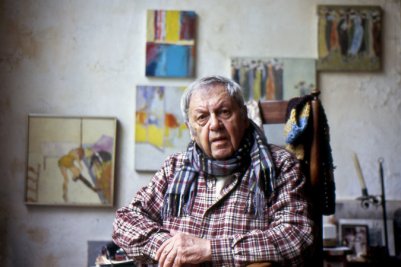

This exhibition is currently on the V&A, until July 3rd. Paul Strand (1890-1976) is undoubtedly one of the greatest and most influential photographers of the 20th century, particularly in terms of fine art and documentary photography.

A student of Lewis Hine, Strand broke the mould of modern photography (along with Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Weston); with a diverse range of work spanning six decades, covering numerous genres and subjects throughout the Americas, Europe and Africa.

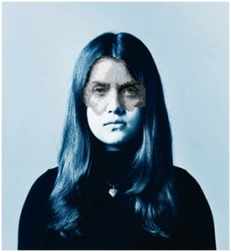

I was not a Strand fan until I saw this exhibition, but would highly recommend a visit to anyone curious about the history of modernist photography and film making. The retrospective exhibition is one of the first of its kind to be shown in the UK on this scale for more than 40 years.Strand had an approach to taking photographs, and worked very much “under the radar” – working without the knowledge of his subjects using a decoy lens on his camera, to fool them into thinking he was photographing something else.

Strand produced many of history’s most era defining images, and people will be familiar with them; even without knowing who took them. For example, Strand’s early work in New York: “The White Fence, Port Kent” (1916) is a nation defining image of America, demonstrating the oxymoron of the fence being apparational and divisional at the same time.

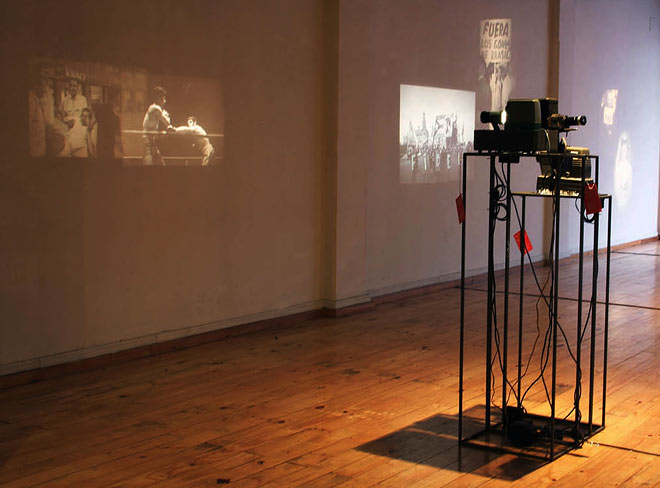

What I found fascinating about the exhibition, was the fact that I forgot I was viewing black and white photography. Each one of Strand’s images spoke to me of depth, and a narrative which is often missing from still photography; but can be attributed to his interest in the moving image. He had an eye for composition, shape, light and structure; that made his work stand out. In turn taking photography into a new direction, and inspiring the likes of photographers such as Ansel Adams; whom Strand shared alot of his techniques.